For better or for worse, hustle culture has fallen out of fashion recently. The idea of living and dying for your workplace no longer seems like a virtue but a scam created by the billionaire overlords. The covid-19 pandemic showed many people how much of their job is really necessary and how much is simply to prove they’re suffering for their paycheck—and with cultural shifts emphasizing work-life balance, mental health, and anti-capitalism, the resounding message is to prioritize yourself and your well-being over anything else.

It’s not that these messages are wrong. They’re valid, important, and exactly what many people need to hear. But they’re based on the assumption that everyone’s natural instinct is to grind till they die. When a quick Google search of “hustle culture” primarily brings up articles about how to save yourself from it, the underlying message is that it’s the default. You need to be told to stop hustling, or else you might accidentally hustle forever. For many of us, this is really not the case.

“You don’t need to be productive!” a typical anti-grind tweet might advise. “Instead, go for a walk and pick flowers. Make yourself breakfast. Write a poem.” The workaholics may have a hard time believing it, but that’s actually a very productive day to some people. A home-cooked meal? Exercise? Fresh air? Poetry? It’s not just good—it’s an achievement.

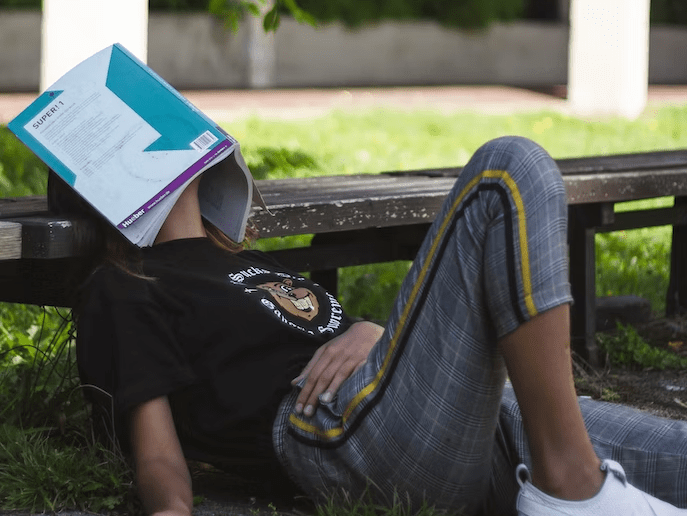

For all the overly responsible hard workers who feel too guilty to take sick days and cope with negative emotions by keeping busy, there are almost as many with the opposite problems. They want to get things done—in fact, most of them have big dreams—but they can’t stop procrastinating, they can’t focus, and they can’t manage their time. A bad day might mean they can’t get off the couch or stop scrolling through their phone. To put aside their feelings to get something done might be one of the hardest things they’ll ever do.

Sometimes depression, ADHD, or a similar issue could be a factor here, but even when these conditions are treated or managed, certain tendencies can still remain. For some people, getting things done is just natural. For others, it’s the single biggest barrier to their success and happiness. Many are somewhere in between.

The idea that the pressure to be productive is a capitalist construct to be discarded isn’t usually helpful either because many people genuinely want to accomplish things. It can be one of the greatest contributors to their self-esteem. The message, “Don’t try so hard,” means very different things depending on who it is directed at. “You are so much more than your job,” is great when you need to slow down, but it doesn’t address the genuine need a person has to express themselves and be useful—and how bad it can feel when you’re somehow unable to do so.

Ironically, some of the biggest sufferers of this problem are people who once seemed to have the most potential. Children who were “gifted” or “high achievers” often find themselves hitting a wall as adults, unable to flourish in the real world. A quick look through the r/aftergifted subreddit shows a pattern of depression, difficulty focusing, lack of motivation, and technology addiction. The alternatives presented to hustle culture aren’t helping these people, and hustle culture itself just isn’t compatible with their personalities. They want to get things done, but this way of trying to do it doesn’t work for them. Why not?

It may have something to do with how they respond to negative emotions. Some people can be motivated by competition, jealousy, or insecurity. These feelings push them to try harder and do better. The idea of working to prove people wrong fuels their fire, and trying to be the best is energizing, not demoralizing. For other, less type-A people, while they could be just as prone towards feeling competitive, the idea that their self-worth is on the line feels absolutely paralyzing. Taking any action becomes infinitely harder because the possibility of doing it wrong has such serious consequences. The additional stress creates a freeze response instead of a fight response.

By now many people are familiar with the idea that procrastination is often not about laziness but perfectionism. The desire to do a task perfectly creates so much pressure that you avoid it completely. There’s no way to live up to your own expectations. But in addition to perfectionism, new studies point towards the theory that “procrastination is a problem of emotional regulation” in general. At the heart of it is a reduced ability to deal with negative emotions, although what those negative emotions are depends on each individual case. They could be anxiety, insecurity, or even boredom. Dr. Fuschia Sirois of Univeristy of Sheffield describes it like this: “People engage in this irrational cycle of chronic procrastination because of an inability to manage negative moods around a task.” Some of the ways that high-achievers motivate themselves, like focusing on the competition and their dissatisfaction with the current situation, don’t work for these people because all they do is increase those negative feelings that they struggle to regulate.

To avoid seeing this as just another way that procrastinators are inadequate, it might be helpful to reframe the issue as a heightened sensitivity to negative feelings. While sometimes this can make it harder to get things done, it can also be a powerful source of creativity. Some of the most profoundly talented artists and writers have struggled with similar problems. All James Joyce’s could manage to write each day was only around 90 words, and even the prolific Meryl Streep describes herself as “an extremely undisciplined person.” The tendency to ignore your feelings and get to work, while necessary sometimes, has its own share of downsides.

Work that matters to you can sometimes be harder to do. Thomas Mann defined a writer as “a person for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.” Caring more can be both a tremendous asset and a barrier to overcome when it comes with anxiety and perfectionism. Some people struggle to motivate themselves to engage in any work they don’t care about, which, while it can lead to work other people consider important being undone, can give them incredible drive and passion in areas they prioritize. It can be their greatest strength and their greatest struggle, depending on how they use it.

Although it has been established that people who struggle with procrastination and getting things done are dealing with negative emotions around whatever work they avoid, it may be unclear what else they have in common. There seem to be big differences between someone who avoids work because of crippling anxiety and perfectionism and someone who avoids it because it doesn’t interest them enough. But actually, caring too much and not caring enough are two sides of the same coin. In both situations, the problem is in the emphasis placed on the end goal. Anxious procrastinators are intimidated by the end goal. They fear they won’t be able to achieve it to a satisfactorily level and become demotivated. On the other hand, disinterested procrastinators cannot overcome their lack of interest in the process just because the end goal should be worth it to them. The abstract final destination isn’t enough to spur them into action. What the two have in common is that focusing the outcome doesn’t motivate them in a consistent way.

According to research, procrastinators “are motivated by factors other than achievement.” This might seem strange, even to procrastinators themselves, because most really would like to achieve things. It’s not that they don’t care about achievement—it’s that it doesn’t motivate them to complete tasks the way it might someone else. Most of them have wanted to be accomplished, successful individuals their whole lives but keep falling short not because they don’t want it enough, but because that’s not the type of approach that works with their brains.

The good news is that there is another approach that does work. Instead of being result-oriented, the solution is to be process-oriented. This might not sound ground-breaking since many of us have been told to “fall in love with the process” before, but that’s because most people don’t take it far enough, and they don’t realize how helpful the concept can be when it’s taken to the extreme. It works for both types of procrastinators, although it may need to be implemented in different ways.

Let’s look at the anxious procrastinator first. When the most common, research-backed advice for getting things done is to set goals, the idea that goals are the root of this person’s problems seems counterintuitive, but it’s true. Remove the goal and most of their anxiety will go away. End results can, even should, be ignored completely. Instead of deciding to learn a skill, write a book, or even to lose weight, this type should ask themselves what habits they would like to adopt. They might decide to “become a person who writes” as a goal, setting aside time in their calendar to write however they feel most comfortable, with no required word count or pressure to create a finished product. Telling themselves, “Now is the time to finally write that bestseller everyone told you you could write in high school,” is the surest way to create a writer’s block so strong no wrecking ball could break through it. Instead, anxious procrastinators should take inspiration from Emily Dickinson and Vincent van Gogh, who became great successes only after they died. Nothing quells their fears and removes the paralyzing pressure they’ve placed on themselves like the idea that they can be a complete failure in this life and yet somehow go down in history as a genius.

This type is filled with so much shame that the ways other people keep themselves accountable can just seem like bullying to their sensitive psyches. For example, if they want to get in shape, weighing themselves or closely monitoring gym progress might only remind them how far they fall short of their own (likely unrealistic) standards. This triggers a shame spiral that makes them more likely to order a pizza than go back to the gym. A smarter approach would be to decide, “I want to be a person who goes to the gym,” and then allow themselves to do whatever they want there. The fear of failure is removed because the only way to fail is not show up. Once you’re there, you’ve succeeded. For people who hate failure, an easy, built-in success is addictive. The self-acceptance required to put results to the side goes a long way towards reducing the shame that creates this perfectionism in the first place.

These strategies will be helpful for most procrastinators, but for those who avoid tasks they find boring or unpleasant, a few additional techniques might be necessary. A lot of advice will be geared towards making the activity fun or interesting, and while that may work, sometimes it serves only to drag out task longer than necessary. People aren’t dumb. They know that cleaning their room is never going to be as fun as a video game, and they know that whatever reward they promise themselves at the end they can just take now. A better approach is to try to make the task go as quickly and painlessly as possible.

First, consider the best and easiest way to accomplish it. The job may seem overwhelming because you don’t know what it involves. Break it down into steps and look for things that can be eliminated or made easier with technology. Do some research, either online or by asking people in real life how they work. Some of their shortcuts may surprise you. The most organized people don’t endure hours of tedious work their “lazy” counterparts can’t handle. They plan in advance so they never have to do that at all. Procrastinators are actually some of the hardest workers of all—because they make their work so much harder than it needs to be.

Next, create a plan that will be as easy as possible for you to follow. Make it so easy you could follow it on your worst day. A plan like that means minimal effort put in more often, so you will need to start early. If you’re used to pulling all-nighters to complete an assignment, instead start three weeks early and work for 10 minutes every day. Set reminders on your phone or create a digital calendar, because you absolutely cannot be relied on to do it otherwise.

For both long-term projects and simple, tedious tasks like housework, utilize timers. Work expands to fill the available time, so challenge yourself to see how much you can do in a short period. Focus on quantity, not quality, because it’s better to do something poorly than not at all. Going back later to improve it requires less mental energy than creating it from scratch.

Consider also whether the actual task at hand is really so bad, or if you share traits with the anxious procrastinator. Maybe what’s so off-putting is how much work there seems to be between you and your goal. Learning a new language, for example, might feel very unpleasant, but memorizing five vocabulary words a week isn’t difficult for anyone. What’s difficult is sitting there thinking about how much you still don’t know. But when you genuinely release your attachment to the result and see the habit as an end to itself, the process can become enjoyable—which means you’re much more likely to stick to it. You won’t speak Spanish tomorrow, but you might in a few years, whereas if you put too much pressure on yourself it’s more likely you’ll never learn it at all.

People may laugh at you if they find out you set such small goals. You might be laughing at yourself, embarrassed that you can’t “just do things like an adult.” But you shouldn’t try these methods to be “nice” to yourself or do things the easy way. You should try them because they work. You didn’t choose your psychological makeup any more than the person who thrives on competition and naturally wakes up at 6 AM. You won’t change it by fighting it. You wouldn’t treat a cactus like a rose bush, so stop following advice that isn’t designed for you. A square peg has just as much to offer as a round one, in the right place.

Some people fear that self-acceptance will remove their desire to improve, but really, the opposite is true. It is only when you embrace where you already are that real, lasting change is possible.