We live in an era marked by addiction, whether it be to opioids, pornography, Instagram likes, or plastic surgery. We view addicts as outliers, and characterize addiction as an illness. But what about the most common addiction of all—smartphone addiction?

No one is shocked if you announce you’re addicted to your phone. If anything, it’s more shocking to not be addicted to your phone. We accept it as a fact of life, something that everyone tries to fight but inevitably fails at. It’s easier to ignore than other addictions because the effects aren’t as dire as drugs or alcohol, so fewer people hit a rock bottom that forces them to change. Parents don’t campaign in the streets after losing their child to an iPhone. But that doesn’t make the issue less serious—it makes it insidious, slowing taking over our lives before we know what’s happened to us.

The statistics paint a disturbing picture. The average American smartphone user spends 5 hours and 24 minutes each day on their phone, checking it once every ten minutes. Phone time increased 39.3% from 2019 to 2022 and continues to rise. While some phone usage is increasing because it replaces other technology (for example, people now spend more time on their phone than they do watching TV), the addictive nature of the phone leads to more screen time overall. People now use their phone to browse the internet more than a computer. In 2011, average internet usage was 43 minutes on a computer and 32 minutes on a mobile phone. In 2021, the average on a computer was 37 minutes. A slight decrease, but phone internet access increased to a whopping 2 hours and 35 minutes. So, while people use computers and T.V. less now, what’s really happening is all of this screen time and much, much more is being done on their phones instead.

But how concerned should we be by these figures? Technology in and of itself isn’t bad; on the contrary, it’s usually very good. If people 100 years ago were told they would be able to access all the world’s knowledge from a device in their pocket quickly and easily, they would be hard-pressed to imagine any downsides. (And if they did come up with some, they probably wouldn’t have been the ones we’ve ended up dealing with.)

Unfortunately, the data on the effects of screen time is worse than most people realize. Brain scans show being addicted to a screen literally changes the structure of your brain, diminishing grey matter in parts of the brain responsible for cognitive abilities like long-term planning and impulse control. Children exposed to more than two hours of screen time per day (the recommended safe maximum) “score lower on language and thinking tests.” Not only that, research has linked language delays in young children to screen time, with every half-hour of additional screen time resulting in a 49% increased risk of having a delay. Perhaps some of the most damning evidence against devices and children is that iPhone inventor Steve Jobs would not let his children use iPads because of their addictive nature.

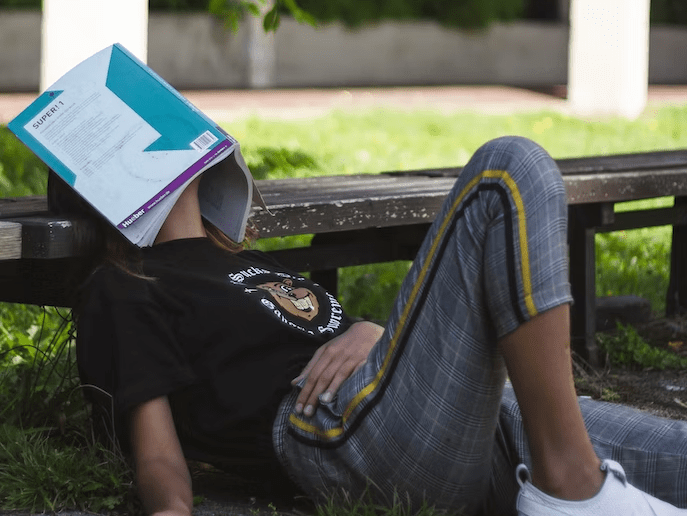

But what about adults? While some of the highest developmental risks are for children and babies with high screen time, adults are still affected negatively. Screen time negatively impacts sleep, mental health, and attention span. Not only that, time spent in front of a computer is time not spent doing something more beneficial, which is why high screen time correlates with less time spent outdoors, exercising, or socializing.

Smartphones are designed to constantly trigger dopamine, the hormone of motivation, which in turn leads to addiction. Addiction is inherently harmful because it diminishes your ability to enjoy time not spent on the addiction. Social media feels more rewarding than real socializing because it’s found a way to turn validation into neat, exciting dopamine triggers—notifications. Real-life doesn’t offer quick rewards, and we end up with shortened attention spans because we’re unable to delay gratification long enough to focus on anything challenging. Because of the way technology hijacks your brain’s reward/motivation center, overuse can lead to ADHD-like symptoms. Children with increased screen time have a 7.7 times higher chance of exhibiting ADHD symptoms, and anecdotal evidence shows adults who “dopamine detox” can radically improve their ability to focus and stay motivated to complete difficult tasks. While some research suggests that screen time does not cause these issues but instead is more likely to be used by people with ADHD, this only reveals another sinister side effect of technology: The most vulnerable are the most susceptible to being harmed by it.

All forms of addiction are related to a difficulty being present with your current reality. Life feels like too much to handle without something to soften its blows. “The world looks so dirty to me when I’m not drinking,” Kirsten Clay says in The Days of Wine and Roses. Any addict can relate to that statement. If their addiction were lifted out of their life, a big, frightening hole would remain in its place. Even when your drug of choice is your phone, life without it feels like a depressing and scary prospect. You are left without anything to save you when you feel bored, lonely, or sad. You have no safety net to help you numb yourself or unwind when things get bad. No more entertainment or satisfaction without putting in effort. It’s like taking a pacifier away from a baby.

Giving up an addiction might be one of the hardest things you’ll ever do, especially when it’s something you can’t cut out of your life completely. But it’s definitely not impossible. Instead of trying to shame yourself into using your phone less, use the following tips to develop a strategy to get your screen time down to a healthy amount.

1. Prepare substitutes.

Nature abhors a vacuum. You can’t remove screen time and put nothing else in its place. You need alternative forms of entertainment, and you need to make them as easy to access as possible. Buy books, take up a hobby, or try watching a movie. Even though it’s still screen time, it doesn’t fracture your attention span the same way. When you’re waiting somewhere with nothing to do, bring out a book or a magazine, or even some knitting. The key is to make this as enjoyable as possible. Now is not the time to force yourself to read Shakespeare. If you like romance novels or Cosmopolitan magazine, read those. If use your phone to look at Instagram or Pinterest, look at books full of photographs on whatever topic you’re interested in. Start with something easy for you to get into and make it available.

2. Fill your time with something else.

People naturally use their phone less when they participate in activities that engage their interest. Many people notice a sharp decrease in screen time when they travel. Make yourself busier, and you’ll naturally be less tempted to use your phone. Think about what you’d like to spend your free time doing and find ways to put these things in your schedule. For people who are heavily addicted and likely to cancel plans or activities to stay home with their screen of choice, find ways to hold yourself accountable. Involve a friend in your plans, book an activity in advance that you have to pay for, or at least change the scenery. Going to a different location can give you the push you need to focus on something else.

3. Physically make your phone harder to reach.

When screen time is over, put your phone in a box across the room. Yes, you can still walk over there and get it, but people are lazy, and it also gives you an extra 30 seconds to think about whether getting your phone is really the decision you want to make right now.

4. Use different hacks to make your phone less enjoyable.

Some people put switch their phone to grayscale (in Accessibility settings), finding it takes the joy out of using it. Others use a variety of screen time limiting apps that can ban you from accessing different apps after a time limit has been reached. Think carefully about how you use your phone, and delete apps that are the biggest offenders—the ones that waste your time without providing any real value to you. You may not want to deactivate social media entirely, but deleting the apps on your phone and using them on your computer instead can help you reduce the time you spend on them. First, computers aren’t as addictive, and second, you can’t take them out every 10 minutes. This can be a good compromise for people who feel terrified by the idea of not using social media completely.

5. Be intentional about your usage.

Your phone can be an amazing tool, and it would be a shame to stop using it completely. Don’t aim for that—aim to make your screen time count. Every time you pick up your phone, set an intention for what you’re going to be using it for. This can help reduce mindless scrolling. You can also arrange for designated phone times after completing tasks throughout your day as a reward. This reinforces your ability to delay gratification and makes the actual time spent on the phone more satisfying. During a period where you don’t touch your phone, you can write down random things you want to look up or do on your phone on a notepad instead of actually doing them. Then, you have a list of tasks to help you stay on track when the phone comes out.

6. Use more technology.

It might seem counterintuitive, but using the right technology can help you use technology less, just like how aimless browsing is reduced on a laptop. Many people report that having an Apple Watch or other smart watch helps them reduce their screen time because they can check their notifications without going into their phone. Smart watches are designed to be functional, not addictive. They allow you to leave your phone out of sight without worrying that you missed an important phone call or message.

7. Schedule your time.

Many people get sucked into their phone and lose track of time. Some of the people most negatively affected by phone addiction struggle with some level of time blindness (often a symptom of ADHD). Many people struggle to calculate and visualize time the way their more punctual, organized counterparts do. Shaming yourself to be better tends to only make things worse, so instead tackle the issue in a productive way. Find ways to make time more visible to you. Set screen time reminders or task reminders on your phone. Create a schedule for your day to help you avoid spending hours on your phone, possibly using Google Calendar, which will keep you on task by sending reminders to your phone. Many people simply make to-do lists, which is not effective because it still leaves it up to you to decide when everything must be done. Reduce the number of choices you need to make on the spot, because more often than not, you’ll choose whatever lets you stay on your phone longer.

8. Remember that the real world is not in your phone.

The more time we spend on our devices, the more the world inside of them starts to feel like reality. It can be hard to reduce social media because of FOMO. But the truth is, the only people who are missing out are those who spend their time on their phone instead of engaging with life. Your phone is not real. Images on Instagram are not real. The lives people project on social media are not real. The people who cancel celebrities on Twitter are just flawed human beings in real life who would probably get cancelled themselves if all their private business was aired. The way people act online isn’t even how they act in person. It’s all an illusion. Your physical health, mental health, productivity, and motivation are not worth sacrificing for an illusion.

Technology is a tool that gives us unparalleled opportunities, but with that comes opportunities to abuse and misuse it as well. It can be hard to see just how much we are now capable of achieving because our brains are not evolved to handle the complexities of modern life, but we live in a time where it is truly possible to become whatever you want to be. But the first step to all of this is freeing yourself from addiction.